The world is full of magic to be discovered, and it was my children’s library and laboratory during their childhood years.

I would like to begin by saying that I am not an educationalist, but my children’s father is. He has a Bachelor of Education degree from King Alfred’s College, Winchester, but the best of his education philosophy (in my humble belief) comes from his mother.

My mother-in-law was brought up in a poor part of South East London. Her mother was a Spanish immigrant who did not speak much English and went blind when my mother-in-law was 11. The war came soon after that, so my mother-in-law had a very low level of formal education. She worked as a cleaner, cleaning offices and schools. But she self-taught, despite her limited hours, to better herself. She finished her years of work as a clerk at London Electricity Board, a huge achievement for a girl who did not go to school and had a lot of responsibilities.

The great thing about my mother-in-law is, she did not harangue her blue-eyed boy to study, study, study. And so, my children’s father grew up cycling round the Kent countryside from the age of 4, played with the family pets, and later on, jammed away in a rock band in some mate’s garage. He is the most balanced, happiest person I know, and he learned a lot and earned enough to buy us a magical life.

When my kids were young, we did not have enough money to keep up with what other families were doing. Thus, my kids grew up without electronic toys or even a colour television. We had to ‘make do’. Pots, pans, wooden spoons when they were young, and later, family games of Pictionary and Charades. We built forts from blankets and sheets, collected interesting things from our walks for our Seasonal Nature Table, and from this way, we all learned about ourselves, the natural world, family values and the beginnings of language, literature, the sciences.

Later, when iPads became the rage, we could have afforded it but somehow never got around to buying it for our youngest child. Her former school had made it mandatory for each student to have an iPad, the much touted learning tool, but she did not do too badly without ever having owned an iPad.

We had to work harder as parents because we did not have the whizzy gizmos to educate our children. We don’t use the internet to babysit them either, so much as the temptation was there to allow them to passively learn from the ‘Net, we taught them the old fashioned way, namely by experiences in the real world.

My second son built a real-life go-kart with his father in the garden shed. He raced the go-kart, became quite good at racing, and then sold it for profit. He wasn’t an academic child, and he certainly did not leave school with a string of A’s, yet he managed to win a scholarship to study Mechanical Engineering & Electronics at Southampton University, and in a time where there are many unemployed graduates, he is second in command of all the weapons on a Royal Navy warship. He is 27, exuberant, boisterous, balanced, loves life.

His younger sister is enjoying the closing years of her very magical childhood, living in a land of aquamarine oceans, blue skies, winding island roads. She rides shotgun to school everyday with her father, chatting away happily, and often, with her mother too. She talks about her day, uncensored, with passion and heat. The teachers were sometimes unfair, there were bitches in her school and dumb boys. History and English Literature are confusing, Maths is boring, and the Sciences are easy. As for English Language… “don’t get me started” with a roll of her eyes.

Unbeknownst to her, as we soothed her, answered her, rebuked her, we are teaching her. Not only about the syllabus, but our family values, the ways of the world, humanity.

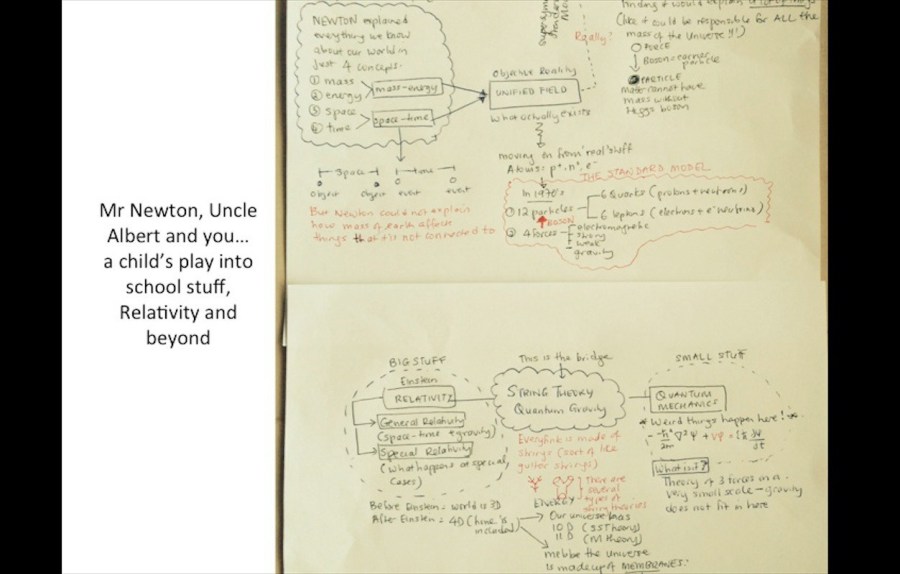

And because we limit the time she is allowed to spend studying, she dives on her books with great gusto. And because she is only allowed limited time on her subjects, she on her own accord brings them into her real world, in our car conversations and whenever she makes the connection with the real world. And her eyes and quicksilver brain are always searching to make the connection, sometimes between the most innocuous events and objects. A casual conversation about “those shoes” became the laws of Spanish grammar and ultimately, the trivium. She argues heatedly, sticking her head between her parents’, intent on getting her point across.

We see the joy of learning awakens in her, and it is a great feeling.