People are often confused about my education philosophies. My children’s father and I are both unapologetic beach bums living on the paradise island of Phuket, with no ambition beyond walking the beach each day. Our older children have all grown and flown the nest, back to our home country (UK) and making strides in their adult lives. Now, there is only Georgina left. She is our last child, and her father and I are living the last years of our parenting journey with her (or should I say, through her).

We both have seen a lot, as one does with over a decade of travelling, living in foreign lands, meeting unusual people and raising five kids. Oh, the wisdom we have acquired from the road, it is nothing like what the books tell you. Of course, as parents, we want to impart the real-life wisdom to her – after all, what parents don’t.

A couple of the important things that we have learned: happiness is internal (therefore don’t go chasing big job titles) and in a world that has become increasingly fast-paced, we have to hold on to good old-fashioned values. And thus, we tell our child, you get the best learning at home (well, on the beach) and in church.

But here’s our dilemma – we have a child who is gifted (I hate the word) and who storms ahead, propelled by her curiosity of the world around her, her impatience at not knowing answers, and her desire to rule the world and see her name in lights.

With the benefit of hindsight, experience and years on the road, we want to tell her this: a lot of what you obsess about is not important, anymore than exam grades are.

Fortunately, we live on a holiday island and she attends a progressive British international school, so the focus on exams is missing from her psyche. Thank goodness. I could not have coped with exam stress for the second time in my life (coping with my own was bad enough), and exams say nothing about a person’s capabilities anyway. I give you an example: despite her tender years, Georgina is one of the most erudite, vocal and critical thinkers I know, and English is her mother tongue. Yet English Language is one of the subjects that she consistently scores lowest in exams.

But dear parents, it does not mean that we just let our child’s fertile brain just rot. We teach her. Teach as in giving her the building blocks to build her own framework, rather than telling her what she has to know. Because a lot of what we know is rubbish anyway, come tomorrow, but the learning process remains and paves the way for future, yet-to-be-known experiences.

Here’s what I mean: whilst I was at Oxford, the superstar of the Astrophysics department was a young scientist called George Efstathiou, who was heavily lauded for discovering cold dark matter. A few years later, his theory was found to be flawed and cold dark matter was dead. And then, it revived again….it goes to show that nobody really knows The Truth, not even parents.

Georgina’s father has a Bachelor in Education degree, so I derive some degree of comfort in the fact that at least one of us know what he/she is doing when it comes to educating this child. We want to educate her for a better world (she, and all the other youngsters, are our world). It sounds rather pompous, so in company, I always say, “Education for tomorrow”.

And this is it about education for the new world: our children are going to grow up to be someone’s husband/wife, parent, employee, employer, leader, friend, helper, and a whole gamut of unofficial occupations. Look around you at these people in your life – what do you love and cherish about them? What do you admire about them? What is it about that special person that makes the world better?

Now turn the mirror inwards to your parenting self. Are you raising that wonderful person, or are you too obsessed trying to create a genius out of a moderately clever child?

I often post on social media about the challenges of raising a child who does not want to follow her parents’ footsteps and live on the beach, existing solely on love, fresh air and sunshine. I post about her asking questions on isotopes, grammar rules, marine plywood, universal proof and a whole lot of other things that are quite frankly beyond my rusted brain. I often struggle to find the answers and have invested hours rereading my old books and doctoral thesis to bring myself up to date.

However, my intention is not to create a monster – sorry, I mean genius. I have no ambition whatsoever of raising a scholarship student either. And there is nothing I find more irritating than a precocious child spouting rubbish that he/she had picked up from the Internet or from reading unsuitable books – the saying ‘empty vessel makes the most noise’ springs immediately to mind.

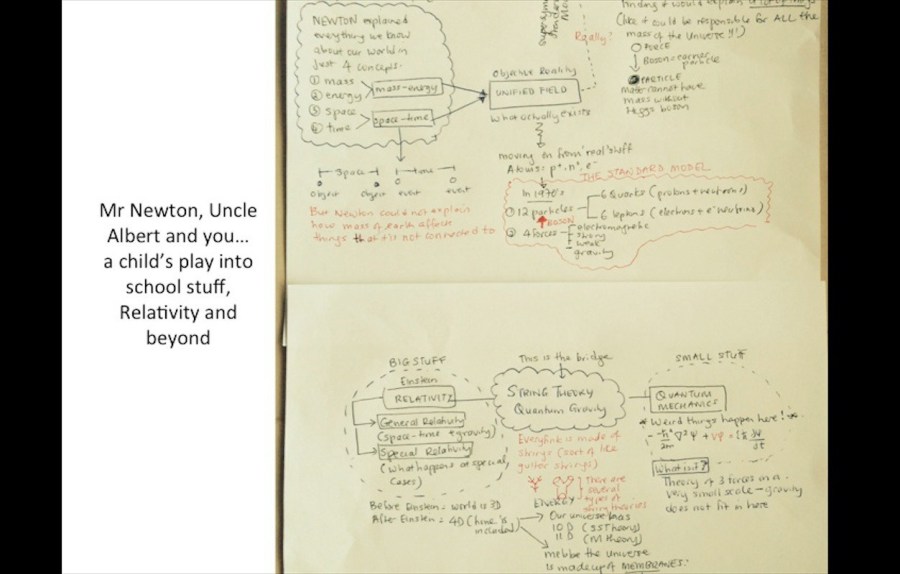

No, we teach our child to learn. Relativity, Quantum Theory and other big-ticket topics that fire the imagination are merely tools for learning, and not the actual Holy Grail. These subjects teach a child that the world is not known, much as we like to think it is, and orders are rapidly changing. This is why Ptolemy is proven wrong, whilst Einstein’s legacies are work in progress. Learning how to think is expansionist and cannot be converted from textbook learning. It is from a different branch all together.

For background, Claudius Ptolemy was an influential mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer and poet. Ptolemy was famous for a number of discoveries, out of which the most famous was a theory that expounded that the earth was the centre of the universe (though some might argue that Ptolemic system holds true for some isolated cases). We now know that the earth is not at the centre of the universe, and nor is the universe the centre of other universes. There is no centre, though no one knows for sure, not even the ‘experts’ with their space-age, multi-billion dollar toys. And this is what I answered to a mother today who suggested that I seek experts to help my daughter with her maths: there is no expert, and the best teacher for a 15 year old child is her parents. Maths knowledge – or any non-contextual knowledge for that matter – will not make her a better person, or a happier one, or a successful one, if your definition of success is a balanced, productive adult with a fulfilling personal life.

I was once asked, when I was giving a talk at the Science Museum London, what I thought about Einstein’s Relativity equations. Thinking on my feet, I responded immediately, “They kind of work, because Einstein left gaps in it for things that he did not yet know.” I was terrified of being misquoted afterwards, as it was a high profile event and I shared the stage with Professor Michael Rowan-Robinson and A.S. Byatt. To compound my worries over my unscripted grandiose statement, the ultimate head of my department at that time was Professor Christopher Llewellyn Smith, who was the Director General of CERN, the European multi-billion pound research facility in Geneva. The dressing down never came (maybe I was correct, but who knows), and a few weeks later, I won the Department of Trade & Industry’s SMART Award.

I don’t use any of it. Except maybe to win arguments with my child.

But this is the important lesson I learned from Einstein: as time passes, we will continue to grow and gain a deeper understanding of things, and we will see things differently. We must allow for the empty spaces in the present.

As my child succinctly summarises, “Oh, the textbooks are not always right then.” And neither are parents.

Real knowledge has to be discovered, either in the real world or within the unplumbed depths of your mind. It does not come spoon-fed to you, either in books or the Internet. And that is what we are teaching our child: to think critically, to question relevantly, to search effectively, to create workable frameworks, and most of all, to find joy in the living and meaning in the caring.

I dedicate this article to my dear friend Richard Boyle, who understands what I am trying to teach my child, keeps me inspired and gives me much joy.